| |

|

|

|

|

|

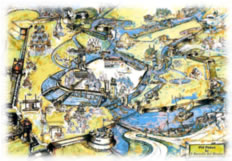

Watercourses and rivers

around Padua Since the earliest times, waterways were preferred by man.  River transportation was considered comfortable and safe, with respect

to roads which often were impassable because of rain, frost and brigandage.

Beside the already numerous natural watercourses, a thick web of canals

was excavated in the Venetian Region. All Venetian towns were linked among

them, and all of them were linked to the Venetian Lagoon and the sea,

major points for trade and exchanges. Navigation in canals

with water slopes and navigation against the stream were made possible

by pulling boats with horses

led by “cavalanti”

(horsemen) or by the boatmen

themselves walking along the river on banks called “alzaie”

(hauling lines).

River transportation was considered comfortable and safe, with respect

to roads which often were impassable because of rain, frost and brigandage.

Beside the already numerous natural watercourses, a thick web of canals

was excavated in the Venetian Region. All Venetian towns were linked among

them, and all of them were linked to the Venetian Lagoon and the sea,

major points for trade and exchanges. Navigation in canals

with water slopes and navigation against the stream were made possible

by pulling boats with horses

led by “cavalanti”

(horsemen) or by the boatmen

themselves walking along the river on banks called “alzaie”

(hauling lines).  To

facilitate the navigation, excavation

of Chambers, dette anche, also called Canal Locks, true ‘water

lifts’ linking watercourses of different levels and allowing boats

to descend or go up the stream were build . Trade and the commercial needs

of the Serenissima Republic of Venice fostered an increase in the demand

for goods and resources from the inland: corn, agricultural products,

wood, marble, limestone from the Hills of Vicenza and the precious trachyte

from the Euganean Hills were transported to Venice by water. To

facilitate the navigation, excavation

of Chambers, dette anche, also called Canal Locks, true ‘water

lifts’ linking watercourses of different levels and allowing boats

to descend or go up the stream were build . Trade and the commercial needs

of the Serenissima Republic of Venice fostered an increase in the demand

for goods and resources from the inland: corn, agricultural products,

wood, marble, limestone from the Hills of Vicenza and the precious trachyte

from the Euganean Hills were transported to Venice by water. Also, the waterways connecting Venice to Padua and to the Euganean Hills were ploughed through by “burci”  (typical

Venetian barges), “padovane”(local barges), gondolas and “burchielli”

(wherries) for the transport of people and goods. Along these rivers country

residences were built; initially intended for the control over the activities

of the farms, they further became wonderful Villas. People used to go

“to the mountains” on the Euganean Hills or would spend their

holidays in the Villas on the Brenta Riviera and the Euganean Riviera

of the Battaglia and Bisato Canals. (typical

Venetian barges), “padovane”(local barges), gondolas and “burchielli”

(wherries) for the transport of people and goods. Along these rivers country

residences were built; initially intended for the control over the activities

of the farms, they further became wonderful Villas. People used to go

“to the mountains” on the Euganean Hills or would spend their

holidays in the Villas on the Brenta Riviera and the Euganean Riviera

of the Battaglia and Bisato Canals. For this purpose, wealthy people would use “burchielli”,

sort of wherries equipped with a cabin with three or four balconies, while

the poorer would make use of soberer and less comfortable boats.

For short distances and for navigation within the boundaries of towns,

Padua as well, gondolas were

preferred. They were furnished with a movable wooden cabin,

called “felze”, giving the boat the aspect and the function

of a coach and offering shelte

For this purpose, wealthy people would use “burchielli”,

sort of wherries equipped with a cabin with three or four balconies, while

the poorer would make use of soberer and less comfortable boats.

For short distances and for navigation within the boundaries of towns,

Padua as well, gondolas were

preferred. They were furnished with a movable wooden cabin,

called “felze”, giving the boat the aspect and the function

of a coach and offering shelte r

from inclement weather and prying eyes. r

from inclement weather and prying eyes.In the Venetian Region, Padua has always been a great “water town”. Built between the River Brenta to the north and the River Bacchiglione to the south, Padua developed in the past an intensive river navigation, thus becoming a reference point for trading activities and transport from the mainland to Venice.  The Brenta River, springing from the Lake of Caldonazzo and descending

along the Valsugana to Bassano, where the plains start, flows in Padua

from the north where it splits into two branches. The first runs straight

into the Lagoon to the south of Venice; the second, the famous Brenta

Canal flows Strà, Dolo, Mira and reaches Fusina and then to Venice.

The Brenta River, springing from the Lake of Caldonazzo and descending

along the Valsugana to Bassano, where the plains start, flows in Padua

from the north where it splits into two branches. The first runs straight

into the Lagoon to the south of Venice; the second, the famous Brenta

Canal flows Strà, Dolo, Mira and reaches Fusina and then to Venice.Noventa Padovana was Padua’s main fluvial port: here boats would stop and people and goods would reach Padua by coaches and carts. In 1209 the 10-km long Piovego Canal was excavated, from Noventa Padovana to Padua. The canal would convey the course of the Bacchiglione into the Brenta, connecting Padua to the Naviglio del Brenta and, therefore, to Venice.  With the excavation of the Piovego Canal and the building of the fluvial port at Portello, river navigation in Padua largely increased. The River Bacchiglione, the old waterway from Vicenza to Padua, was the main water supply for Padua. Padua lived and still lives with the waters from the Bacchiglione which flows into the town from the south, at Cavai Bridge, and flows along the renaissance city walls to the old Ezzelino Castle of Padua, magnificently overlooked by its defensive tower called Specola. The river here splits into two branches. The left branch, called Tronco Maestro, slopes fast along the Riviere of the medieval walls towards the ancient Carmine Church and runs under Molino Brigde, where the river in the past supplied water to watermills, to finally reach the Porte Contarine Lock, where it flows into the Piovego Canal. A second branch of the Bacchiglione, largely covered up today, swerves, under the name of “Naviglio Interno”  ,

at Specola towards the Riviere

within the most ancient city walls, runs through the old town centre and

brushes the old palaces and the University, to then reach the Porte Contarine

Lock. From here its waters jump the slope into the Piovego, where meets

the Tronco Maestro waters. ,

at Specola towards the Riviere

within the most ancient city walls, runs through the old town centre and

brushes the old palaces and the University, to then reach the Porte Contarine

Lock. From here its waters jump the slope into the Piovego, where meets

the Tronco Maestro waters.Another branch of the Bacchiglione in Padua, Bassanello area, runs along the Battaglia Canal, at Battaglia Terme discharge one’s waters into the Vigenzone which passes through Bovolenta and, then, under the name of Pontelongo Canal, flows into Chioggia where its waters mingle with those of the Brenta coming from Strà. |

| top |